The situation: You are working doing website development for a non-profit organization that has patrons/users from several different language groups, English and two others. Describe how you would decide how to deal with providing access to all of the users and how you would convince your supervisors and others that the expenditure for your time and expertise is worthwhile.

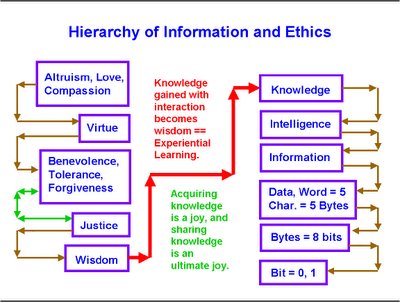

The Potter Box provides a model for making ethical decisions. The model categorizes ethical dilemmas within a four-step analytical framework. By defining the situation and analyzing the facts, “values, principles, and loyalties” (Black, 2003, sl. 7) it is possible to use applied ethics to make complex, socially responsible (Baker, 2001, p. 168) decisions.

The first step in applying the Potter Box approach requires defining the situation objectively, identifying the relevant facts that are at issue in the situation, and providing detailed information related to the ethical dilemma. The facts of the selected situation involve questions about providing web-based access to users from three different language groups, including English. The identified dilemma can be defined in regard to the question of the ethical obligation that does or does not exist on the part of the non-profit organization to provide access to web-based information in languages that all patrons can comprehend. If some patrons cannot understand English, is the organization obligated to present web content equitably (Baker, 2001, p. 164) in relevant languages so that all patrons can retrieve the information provided?

The next step in the analytical process involves identifying the values of the non-profit organization. In this situation, the assumption is that the organization is interested in providing web-based access to all patrons. While the time involved in creating access for people from language groups other than English may be a concern, it is clear that patrons who do not understand English will not be able to use the web-based information unless that information is provided in all relevant languages. Cost-based concerns are not apparently an issue in this situation. If the primary concern of the organization is providing respectful access and autonomy (Baker, 2001, p. 163) for all interested patrons, then providing access that facilitates the comprehension and use of information by all patrons, regardless of their language, is a core value. While English may be a primary and universal language, the result of offering information only in English compared to offering the information in all languages relevant to the organization patrons, means that a limited group of English-speaking patrons will find the organization website useful.

The principles on which the non-profit organization is based can be applied to this situation. If a core value is accessibility for all patrons, then principles of utility dictate that the website should be designed to meet the needs of all patrons, including the presentation of information in all relevant languages. According to John Stuart Mill's “Principle of Utility”, it is essential to seek the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. Based on this ethical philosophy, the organization website should be available in all languages represented by the organization’s patrons. As an additional philosophical consideration, John Rawls' “Veil of Ignorance” requires the organization to consider the perspective of the patrons affected by decisions about the presentation of the website. How will patrons feel if they cannot access the information on the website because they cannot understand the language in which the information is presented? Based on the Judeo-Christian “Persons as Ends” principle, the organization is obligated to follow the “golden rule” when considering the needs of patrons. How would English-speaking patrons feel if they could not read the website? Alternatively, the principle of compromise or “Confucius' Golden Mean” and the principle of moderation or “Aristotle's Golden Mean” emphasize a moderate approach in decision-making. In this situation, compromise and moderation may require alternative methods of providing information for use by all patrons. These time-honored “modes of ethical reasoning” (Black, 2003, sl. 7), clarify how to compare and apply ethical principles to the situation, with the identified values of the organization being regarded as “categorical imperatives” (Wikipedia, 2006) based on maintaining patrons’ trust (Baker, 2001, p. 159) in regard to the issue and options under consideration.

In this situation, the web designer must determine whether allegiance is primarily to the organization or to the patrons. Since the non-profit organization is presumably intended to serve the patrons, the web designer can make a persuasive case for providing information in all relevant languages and not just English. If time is a concern for the organization, the web designer may offer to build the website in English initially, with a plan for adding translation of content to the two other languages. Based on the authentic (Baker, 2001, p. 161) service-orientation of the organization, the time and effort expended on providing web-based information in all relevant languages is in the best interests of the patrons, and therefore the organization.

In conclusion, based on analysis of the situation using the Potter Box model for decision-making, the web designer can confidently make an ethically-based case for presenting the organization website in English, initially and then adding the other two relevant languages. This course of action addresses the essential values, principles, and loyalties according to the facts presented in the defined situation. The ethically-based decision will allow the organization to present the website in a timely manner and also offer web-based content in all relevant languages because “vulnerable audiences must not be unfairly targeted” (Baker, 2001, p. 166). The impact of the decision means that the website will be available in English initially, but will eventually offer information in the two additional languages. Both the organization and all of the patrons will benefit from this decision, because no interests are disregarded.

However, since the Potter Box is “a linked system” (Wikipedia, 2006), the issues related to this situation can be reconsidered and analyzed from different perspectives within a “framework for ethical planning and evaluation” (Tilley, 2005, p. 317). In the situation presented, “the ethical evaluation of a given (decision or) policy requires the evaluation of the consequences of that (decision or) policy, and often the consequences of the (decision or) policy compared with the consequences of other possible (decisions or) policies” (Moor, 2004, p. 108). It is essential to remember that “Policies are rules of conduct… Policies recommend kinds of actions that are sometimes contingent upon different situations” (Moor, 2004, 107). Based on how the situation is defined, and different perspectives on the values, principles, and loyalties involved, different decisions and/or policies could be made to resolve the issues.

References

Backus, N. & Ferraris, C. (2004). Theory meets practice: Using the Potter box to teach business communication ethics. Proceedings from the 69th Annual Convention Cambridge, MA: The Association for Business Communication. Retrieved January 27, 2006, from http://www.businesscommunication.org/conventions/2004Proceedings.html

Baker, S. & Martinson, D.L. (2001). The TARES test: Five principles for ethical persuasion. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 16 (2 & 3), 148-175. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum.

Black, J. (2003). Ethical decision-making models across the professions. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida. Retrieved January 26, 2006, from www.stpt.usf.edu/peec/Decisionmaking.pdf

Moor, J.H. ( 2004). Just consequentialism and computing. In R.A. Spinello & H.T. Tavani (eds.). Readings in cyberethics (2nd ed.) (pp. 107-113). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Wikipedia. (2006). Potter box. Wikipedia: The free encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved January 26, 2006, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potter_Box

Tilley, E. (2005). The ethics pyramid: Making ethics unavoidable in the public relations process. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 20 (4), 305-320. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum.