Critical Thinking

Critical Thinking and Technology

"Henry Smith married 150 women in the course of 10 years. He was never arrested for bigamy although each marriage was witnessed and recorded with the proper authorities. Why?"

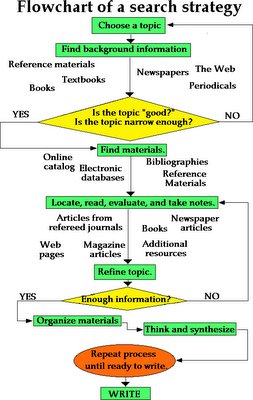

"When you ask students to define "critical thinking," they will often refer to this type of puzzle or brainteaser. And although developing critical thinking skills will help students solve this puzzle, critical thinking skills will also help students as they face crucial decisions in education and in life. Students, and all of us, are bombarded with ideas and with people trying to persuade us to accept the ideas they are promoting. You only have to turn on a television talk show to see this in action. At least when watching a talk show, the viewer is given some background information about the speaker's credentials or lack of credentials and is usually aware of the personal bias that the speaker brings to the topic. The advent of the computer information age has presented us with a new challenge: a wealth of information distributed with few restrictions and often limited information about the author of the material. With the increasing use of web-based technology to gather and interpret information, teaching critical thinking skills to students is even more important."

Definition of Concept & Theory

What is critical thinking? There are a variety of answers to that question, but most experts agree that it includes the ability for a person to use his/her intelligence, knowledge and skills to question and carefully explore situations to arrive at thoughtful conclusions based on evidence and reason. A critical thinker is able to get past biases and view situations from different perspectives to ultimately improve his/her understanding of the world. In those two sentences lie a lifetime of work for an individual, work that begins with a formal education in critical thinking skills. A student once told me, "Whatever you teach me, what I believe is true." This is the crux of teaching critical thinking. It cannot be taught as an absolute. There are no formulas to memorize or tests to take. Teaching critical thinking is about helping students discover the answers. That said, there are some basic tools that you can use to begin to teach critical thinking to students.

John Chaffee in The Thinker's Guide to College Success defines thinking critically as "carefully examining our thinking (and the thinking of others) in order to clarify and improve our understanding." He suggests providing students with practice and guidance in the five activities listed below:

* Thinking Actively by using our intelligence, knowledge, and skills to question, explore, and deal effectively with ourselves, others, and life's situations.

* Carefully Exploring Situations by asking--and trying to answer--relevant questions.

* Thinking for Ourselves by carefully examining various ideas and arriving at our own thoughtful conclusions.

* Viewing Situations from Different Perspectives to develop an in-depth, comprehensive understanding.

* Supporting Diverse Perspectives with Reason and Evidence to arrive at thoughtful, well-substantiated conclusions.

"Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness.

It entails the examination of those structures or elements of thought implicit in all reasoning: purpose, problem, or question-at-issue; assumptions; concepts; empirical grounding; reasoning leading to conclusions; implications and consequences; objections from alternative viewpoints; and frame of reference. Critical thinking - in being responsive to variable subject matter, issues, and purposes - is incorporated in a family of interwoven modes of thinking, among them: scientific thinking, mathematical thinking, historical thinking, anthropological thinking, economic thinking, moral thinking, and philosophical thinking.

Critical thinking can be seen as having two components: 1) a set of information and belief generating and processing skills, and 2) the habit, based on intellectual commitment, of using those skills to guide behavior. It is thus to be contrasted with: 1) the mere acquisition and retention of information alone, because it involves a particular way in which information is sought and treated; 2) the mere possession of a set of skills, because it involves the continual use of them; and 3) the mere use of those skills ("as an exercise") without acceptance of their results.

Critical thinking varies according to the motivation underlying it. When grounded in selfish motives, it is often manifested in the skillful manipulation of ideas in service of one's own, or one's groups', vested interest. As such it is typically intellectually flawed, however pragmatically successful it might be. When grounded in fairmindedness and intellectual integrity, it is typically of a higher order intellectually, though subject to the charge of "idealism" by those habituated to its selfish use.

Critical thinking of any kind is never universal in any individual; everyone is subject to episodes of undisciplined or irrational thought. Its quality is therefore typically a matter of degree and dependent on , among other things, the quality and depth of experience in a given domain of thinking or with respect to a particular class of questions. No one is a critical thinker through-and-through, but only to such-and-such a degree, with such-and-such insights and blind spots, subject to such-and-such tendencies towards self-delusion. For this reason, the development of critical thinking skills and dispositions is a life-long endeavor."

(A statement by Michael Scriven & Richard Paul for the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking Instruction)